Balance and Vision

Our ability to maintain our balance is based on our brain’s ability to integrate input from our visual, vestibular and proprioceptive systems. In this article, we will talk about how our vision is important for balance and what happens when this system is impaired. You can read more about general balance in our previous article HERE.

Humans are incredibly reliant on their vision and it is theorized that when our eyes are open, about half of our brain is dedicated to processing and using visual information that allows us to interact with our environment. While our vision is a powerful system that allows us to maintain our balance, it is closely linked and develops with our vestibular system. When we are born, our vestibular system is the only fully developed part of our central nervous system. Throughout childhood, we use the strong input of our mature vestibular system to help develop our visual system and guide our movement. These two systems work together to produce coordinated and collaborative movements, learning together to interpret our visual environment. As our visual system develops, that role switches and our visual system becomes our main balance system that drives movement. At this point in development, our visual system is so strong that it can even override the information received from other balance systems (vestibular and proprioception). An example of this would be seasickness, if someone is sitting on a boat in rough waters, they can fix their gaze on the stable horizon to override the dizzying feeling they get from their head moving on the boat. Imbalance can be caused by a variety of sources such as a brain injury (traumatic brain injury, stroke, cancer), certain medications or just normal aging. When these 3 systems give our brain conflicting information, it can impact our balance and quality of life.

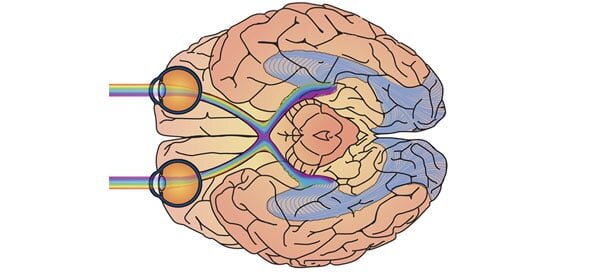

Our vision consists of multiple parts in both the peripheral and central nervous system. In order for us to have good vision, both of these systems need to be intact. The part of our vision in the peripheral nervous system is made up of six muscles controlled by cranial nerves 3, 4 and 6. These muscles allow us to move our eyes in all directions as well as adjust our vision for things close up and far away. All other aspects of our vision are managed by our central nervous system. These functions range from pupil actuation, controlled by cranial nerve 2, to the deep brain structures needed to process visual information. We not only need to be able to have sight for clarity of an image but we also need to be able to perceive and process the information that we see. If you look at the image below, our visual processing runs through the whole length of our brain. It starts with the images we see and then gets bounced through multiple structures until it lands in the visual cortex in the occipital lobe at the back of our brain.

Vision Assessment:

As we just learned, our vision is very complex. If you have any concerns about your vision and how it may be affecting your balance, you should consult with your current optometrist. They may refer you to a specialist, such as an ophthalmologist that specializes in eye disease or a neuro-optometrist. You can also search for a neuro-optometrist HERE.

If you are seeing a physical therapist for dizziness or balance, below are some of the assessments they might use to see if your visual system is a contributor. The vestibular and the visual system are highly correlated and some of the tests for vision and vestibular assessment may overlap. Check out our next blog post that focuses on the vestibular system.

Spontaneous nystagmus:

Tests the eye’s ability to stabilize on a target.

A clinician will perform this test by looking at your eyes in a bright room and darkness.

If someone has difficulty with this task, they may feel dizzy and off-balance in all positions without movement. This is due to an injury in the brain.

Smooth pursuit:

Tests the function of your eye muscles.

A clinician will ask you to follow an object in multiple directions throughout your visual field to assess how your eyes track slow moving objects.

Impairments in this task can result in dizziness when scanning the environment.

Saccades:

Tests your ability to track objects that move quickly in front of your visual fields.

A clinician will ask you to look back and forth between two objects as quickly as you can.

Saccades are slowed in older adults and those with Parkinson’s disease.

Vergence:

Tests your ability to focus your eyes on objects at varying distances.

A clinician will start with an object that is close to your face, they will then move the object closer and further away from you asking if the object remains clear or appears blurry or double.

An impairment in this test can indicate difficulty with depth perception which can impact function in daily life

Visual Acuity:

Tests your ability to see things clearly, testing both your optic nerve but also your ability to process information that you see.

A clinician will generally use a Snellen chart to assess this or an optometrist may use specialized equipment.

A impairment in this will impact clarity for reading, discerning objects and spatial recognition.

Peripheral field test for visual neglect and visual field cut:

Tests your ability to see and/or process your entire visual field.

A clinician will have you look straight forward and move things into your field of vision. For visual neglect, a client may be asked to perform a written test such as the line bisection or clock drawing test.

A visual field cut is when part of a clients visual field is no longer visible to them due to damage somewhere along the visual tract. Visual neglect is usually due to a processing impairment in the temporo-parietal junction of the brain. In general, a field cut can more easily be compensated for because the client understands there is a deficit and can learn how to navigate their environment accordingly. With visual neglect, the client generally has a cognitive impairment that impacts their ability to process what they see, causing a bigger concern for falls.

Visual Midline:

Tests your ability to correctly orient an object to the middle of your line of sight.

A clinician will move a pen from one side of your body and ask you to tell them to stop when it appears in the middle of your nose or eye.

An impairment in this area is usually caused by the brain’s ability to process the information it is seeing. In someone with a skewed midline orientation, they have difficulty with even simple movement tasks because the visual information their brain is processing is not accurate.

An individual with a left sided visual neglect may perform the clock drawing test like this.

How impairments affect function:

According to research, our balance is most significantly affected by two main visual impairments, contrast sensitivity and depth perception. Contrast sensitivity is the ability of the person to distinguish between objects of varying degrees of light and dark. Poor contrast sensitivity is very closely related to difficulty with reading, navigating uneven surfaces such as curbs, driving at dusk/dawn, facial recognition of emotions and tasks of daily living. Poor depth perception will impact one’s balance by impairing their ability to sense their distance from an object, coordinate hand/eye movements, and safety awareness with objects moving around them. Multiple research studies have shown these two impairments to be a high risk for falls for both healthy and neurologically affected older adults.

Visual acuity impairments and visual field cuts have been shown to be primary factors in recurrent falls (greater than 2/year). Interestingly, a self report of poor vision was not found to be linked to recurrent falls, indicating that a full vision assessment by a professional is important when determining your risk of falls due to vision.

Treatment:

According to the CDC website, home modifications have been shown to be the biggest factor to reduce falls in older adults with visual impairments. This can usually be a simple and immediate fix that can be done with the help of a family member. Check out our home safety blog HERE for more information on modifications you can make within your home today to decrease your risk of falls.

If a client has a significant visual impairment affecting their balance then therapy will usually begin in a seated position. This allows a therapist to start with the foundational skills that the eyes need to function without activating a fear of falling. This may be looking at a client’s ability to orient themselves to midline, retraining their brain to focus on objects as they move or strengthening the eye muscles to improve the quality of one’s vision. There are many exercises to help retrain the visual systems within the brain but these would be individualized based on the results of a vision test. The therapist will also likely initiate vestibular exercises to assist in linking the two systems’ inputs again. The therapist will then progress the exercises to make a task more physically challenging, increase the cognitive load and make each exercise more functional. Vision is only one part of our balance system, stay tuned for follow up posts on our Vestibular and Proprioceptive systems!

Crews J, Chou C, Stevens J, Saaddine J. Falls among persons aged >65 years with and without severe vision impairment-united states. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016; 65(17): 433-437.

Davis N. The connection between vision and balance. Vestibular Disorders Association. 2016. 21: 1-3.

Salonen L, Kivela S-L. Eye diseases and impaired vision as possible risk factors for recurrent falls in the aged: a systematic review. Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2012; 1-10.